Back to Basics

- By proadAccountId-377678

- •

- 24 Jun, 2016

- •

Compassion, Care & Community

Download her presentation by clicking on the link below

The dying are some of the most invisible, vulnerable and powerless among us.

If the measure of a society’s humanity is how it looks after its children, the marginalised, the dispossessed and disempowered, then the ultimate yardstick must be how it cares for the dying.

The dying are some of the most invisible, vulnerable and powerless among us.

Care of the dying is an increasing social challenge in Tasmania, whether we are living with a life-limiting illness or not.

Investment in care of the dying is an investment in the living and the future. Sooner or later we will all die and I, for one, would like to know I have been listened to by everyone involved in my care, that my dying wishes will be respected, that I have access to quality, home and community-based end-of-life care, and that I can die how I wish where I wish.

Delivery of palliative and end-of-life care services in Tasmania must adapt to changing times, improve equity of services and better meet rapidly changing expectations. We are poorly prepared for well-documented future needs.

There is now a wonderful chance to plan and make a wise investment in future-oriented palliative and end-of- life care systems, using the State Government budget windfall of $590 million over four years from GST funds.

Creation of a statewide health system is a chance for Tasmania to consolidate its reputation as the nation’s most compassionate, creative and progressive state.

On July 1, three regional health organisations will combine to form a statewide primary healthcare service. This will include palliative and end-of-life care services.

Are Tasmania’s services for the dying, their families and communities up to the task? What needs to change to ensure they are? How do we ensure a client’s dying wishes will be acted on in this new Utopia of care?

The shift from hospital to community-based primary healthcare is a great public policy objective but needs to be accompanied by more investment in services, personnel and resources.

In Tasmania, we have the most rapidly ageing population of any state. We have the highest rate of chronic illness and the most dispersed population, with a majority living outside Hobart and Launceston.

There is a limited range of options to meet the needs of the dying and their families, especially in remote areas.

The Grattan Institute’s 2014 report, Dying Well, says 70 per cent of Australians want to die at home yet only 14 per cent do, and that Australia is behind other developed countries such as the US, New Zealand, Ireland and France.

Changing demographics, expectations and budget priorities, and a lack of options for care, are clear signals an overhaul of palliative and end-of-life care services is timely.

So what might an action plan for Tasmania’s future palliative and end-of-life care look like? My suggested plan, sent to the Health Minister, has 10 key components to achieve equity across the state through an integrated, statewide palliative and end-of-life care system for 21st century Tasmania. It provides opportunities for job creation and export potential for innovative care and educational initiatives.

The priority is statewide, integrated, home and community-based palliative and end-of-life care services that are available to everyone who chooses them. They must be available 24 hours a day, seven days a week, including to those living in remote areas.

There must be government commitment to create additional dedicated, public, end-of-life care beds.

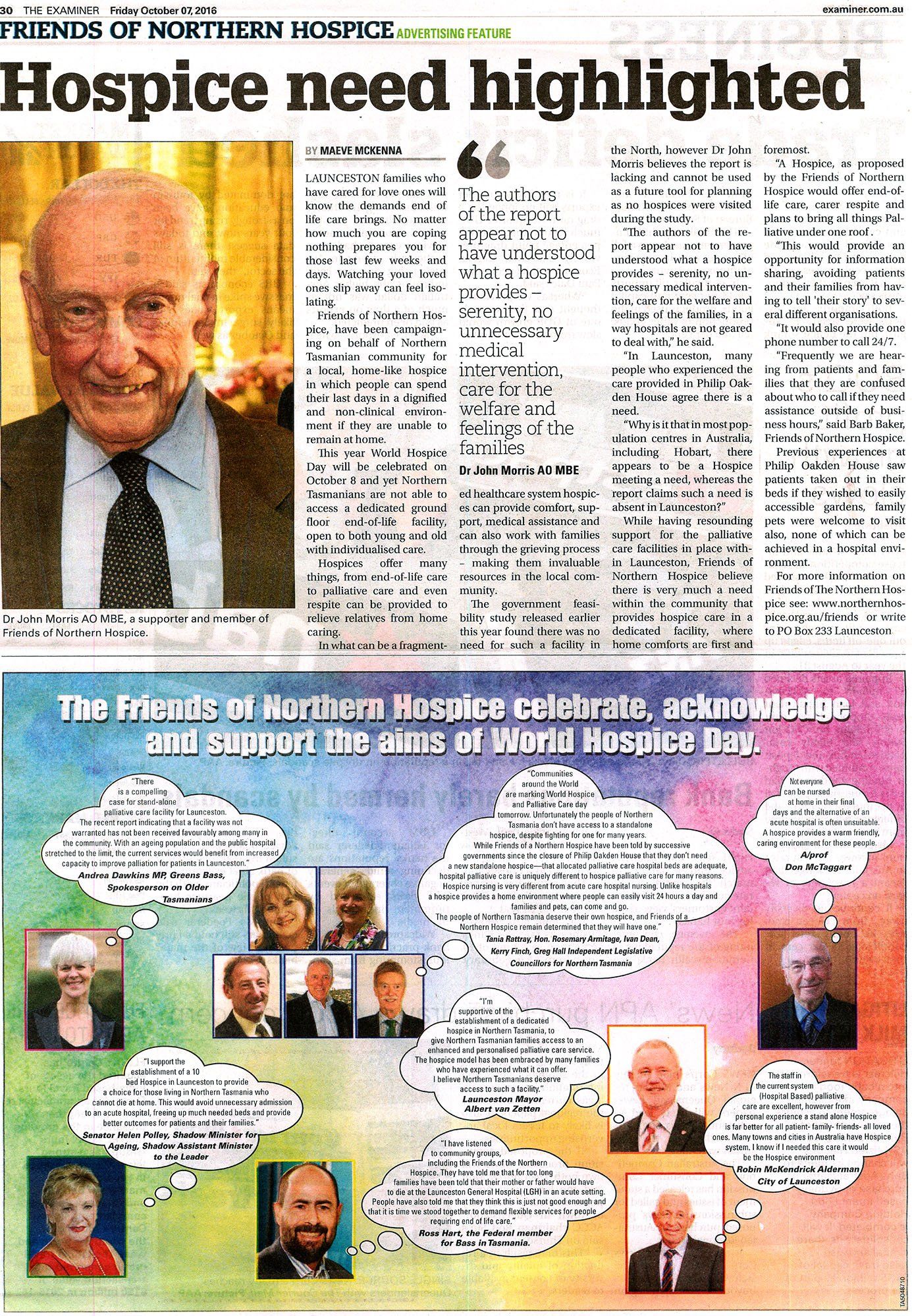

Community hospices should be established in the North and North-West. The Whittle Ward in Hobart is Tasmania’s only purpose-designed hospice. It is on the ground floor, with a home-like atmosphere, fresh air, gardens and children. Friends and pets are always welcome. The Whittle Ward has 10 public beds and serves the state, with clients from as far away as the North-West. This does not work well for the dying and their families who have to leave the familiarity and support of their communities if they need to use the expertise of a specialist facility.

Community hospices should include day hospice and overnight respite facilities.

Community nursing, hospice@HOME and allied health personnel could be co-located for resource sharing and to encourage collaborative approaches to care delivery.

Beds dedicated to end-of-life care in multipurpose centres and district hospitals in regional, rural and remote areas sufficient for the next five to 10 years are also essential to provide an integrated statewide service.

In other states and overseas, community hospices and other end-of-life services are funded by collaborations and partnerships among national, state and local governments and the private sector, and the same can be achieved here. Caring for the dying is a rapidly growing need and nursing homes and private hospitals are well placed to take advantage of this expanding market.

In return, they must ensure quality end-of-life care with investment in palliative care training for their registered nurses and carers and the recruitment of additional staff, including more night staff.

Caring for palliative clients differs significantly from caring for the elderly. Many palliative care clients are not “old” and their needs and expectations often differ considerably from those of aged care clients.

Hospital-based palliative care units are places of last resort if a person cannot, or does not want to, die at home or elsewhere in the local community. There will always be a need for PCUs for complex cases where palliative care specialists and multidisciplinary palliative care teams provide care. But we also need community-based, primary caregivers integrated with specialist services. GPs must be assisted to play a more direct, active role in client care, including in palliative care units and community hospices. More often than not, GPs have known clients and their families before they develop a life-limiting illness. They are trusted by the family and will continue to see family members after the client has died. Trust, ongoing family contact and continuity of care encompassing birth, death, bereavement and grief are of central importance to families.

Frontline allied health workers such as social workers, physiotherapists and occupational therapists, are equal and valued partners in multidisciplinary palliative care teams. Additional frontline, palliative care social work positions need to be created across the state as a matter of urgency to ensure the success of the transition to community-based care and to offset recent cutbacks in frontline community palliative care social work positions.

Family and informal (unpaid) carers, and community and hospice volunteers are highly valued by clients and communities as an essential support service for the dying and their families. They should not be treated as a free labour force by cash-strapped governments.

On-the-ground services can be supported to stay relevant through quality research and a collaborative, multidisciplinary educational program focused on building the skills, capacity and resilience of Tasmania’s communities in addressing end-of-life care.

I would like to see a Centre for Excellence in End-of-Life Care Education and Training established at the University of Tasmania. An independent, statewide, consumer advocacy group would be a valuable asset. There is presently no organisation in the Tasmanian palliative and end-of-life care sector that has the key goal of protection and promotion of consumer rights.

The State Government must ensure end-of-life services are equitable, appropriate, accessible and able to deal with changing community expectations in the 21st century.

Equally important is a genuine commitment by the Government to those who are living with a life-limiting illness, their families, carers and local communities so that they will be guaranteed a voice in shaping and implementing their future care.

Dr Rosemary Sandford is a university associate at the University of Tasmania, a hospice volunteer and past president of the Tasmanian Association for Hospice and Palliative Care.